In this story from the July 2019 edition of Australian Aviation, Stefan Drury writes about his experience practicing emergency scenarios in a flight simulator.

“Sim training is pointless.”

That’s what I was thinking before my session in the Cirrus simulator. Though, to be fair, I should expand on that thought a little. What I was really thinking was: “Sim training is pointless – BUT, I can film the experience and it should make an interesting video for my YouTube channel. So, I may as well give it a go.”

I’d booked the sim session at Moorabbin Airport in Melbourne’s south-east with my Instructor Michael Walden a week or so before, after we’d spoken about practising emergency situations in the Cirrus. We sometimes practice engine or equipment failures when we’re out flying together or during routine checks like a biennial flight review or my yearly instrument proficiency check. Plus I have a commercial pilot licence so you could say I’ve been through my fair share of simulated engine failures in the past.

This experience combined with the fact I always brief myself on what I’d do in the event of an engine failure after takeoff before every flight meant I felt fairly confident I’d know what to do if something went bang in the simulator. And if all else failed I could simply lean back on “aviate, navigate, communicate. Fly the plane”.

So heading to the simulator session I thought I’d focus on making a video of the experience to share with my YouTube viewers and, as a side benefit, perhaps I’d also learn a thing or two for my flying in the process.

The simulator at Avia Aviation is a full-motion multi-axis beast which can simulate not only pitch/roll movements like you’d expect but also acceleration and deceleration forces to make movements such as takeoff or braking on the runway feel very realistic.

I settled into the left-seat and started setting up my cameras. Mike was sitting behind me configuring the computer to simulate a series of emergency procedures. I was pretty confident I’d get an engine failure on the takeoff roll, then probably one on climb-out as well. I mean those are the big-ticket items, right? I’d visualised what I’d do in both events so as I set the GoPros rolling and shot a quick introduction I was feeling pretty good.

Mike set the airport to Moorabbin, I pushed the throttle lever forward, and off we went. I was trundling down the runway and thinking “this is pretty realistic”. I could feel the acceleration and the bumps of the wheels rolling across the surface. I watched the landscape flashing past me enjoying the sensation of the takeoff roll and waited for Mike to click a button and fail my engine.

He didn’t. So I assumed we’d be taking off. “Maybe this is an engine failure after takeoff” I thought. I continued to accelerate down the runway enjoying the very realistic motion sensation from the simulator and got ready to rotate. I glanced down to my airspeed indicator to confirm we were close to my rotation speed of 70 knots which was when I suddenly realised my air speed indicator was reading 0.

I’d been so focused on one big emergency (losing my engine) that I’d completely failed to notice the smaller but significant fact that my ASI had failed. My wheels were still on the ground, so I knew I had to close the throttle and stop the aircraft on the remaining runway. The rest was fairly instinctual – throttle back, firmly but gradually apply the brakes, keep it straight, and bring my Cirrus to a standstill with the end of the runway and the airport boundary just in front of me.

“This is going to be harder than I thought”, I thought.

Mike reset the sim and got me to takeoff again. I pushed the throttle forward and my eyes moved straight to the airspeed indicator. “Airspeed alive on both” I called out (I do this now EVERY TIME I start rolling in the SR22, checking I have an airspeed reading on the PFD screen and on the standby ASI). Engine temperatures and pressures in the green (I do that one after I had to abort a takeoff once due to a low oil PSI reading). Reaching my rotation speed, I pulled back on the stick and we started to climb.

“Positive rate of climb, no obstacles, flaps away” I called out, trying hard now to remember after every takeoff to check and not be distracted by the simulator.

And then the engine failed. Well no that’s not entirely accurate. It didn’t fail, it didn’t stop, it just kind

of spluttered. Then coughed, then came back to full power . . . hooray. Then lost power again . . . gah! Then came back, and so on. I watched the engine power needle flick between 100 per cent and 0 (and several positions in between) and quickly realised whatever power I had was not keeping me airborne, I couldn’t maintain altitude.

This is many pilots’ worst fear – a partial power loss after takeoff. A total loss of power (or a total loss of anything) usually means you go straight to the “what do I do when I lose X” checklist or procedure. However, a partial loss has your brain sitting in that middle ground of “what if it comes back”, “can I make it round the circuit and land”, or “if I leave it a few more seconds will it go away”. Each of those soak up the one resource you never have enough of in an emergency situation – time.

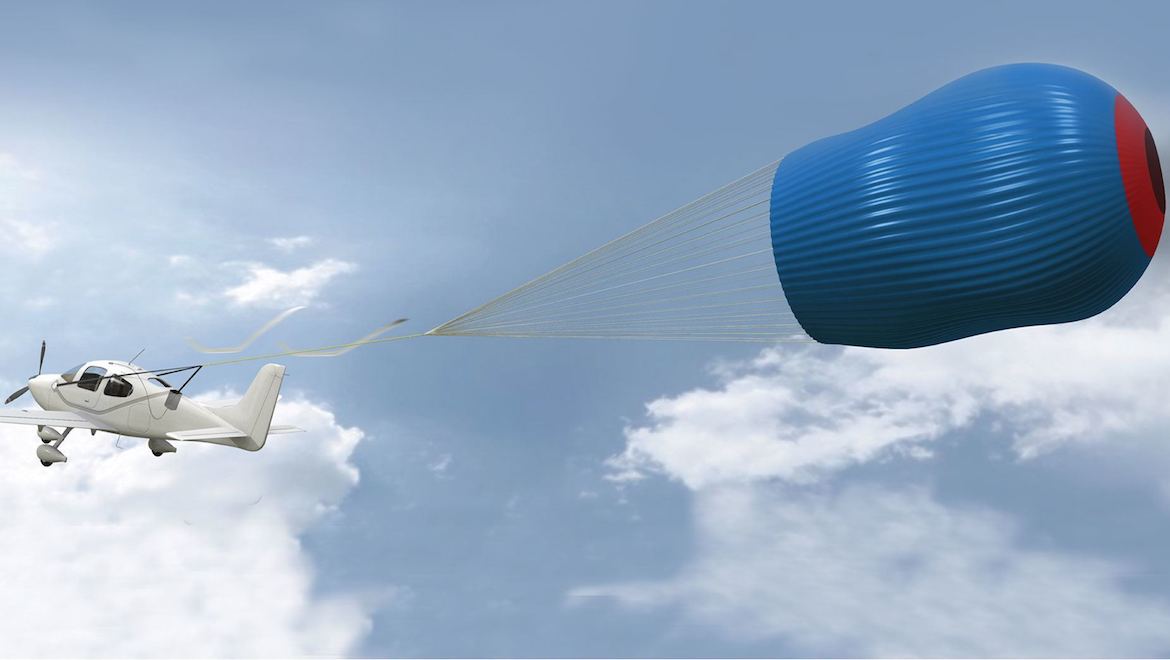

I looked at the altimeter and realised I was less than 600ft AGL. In a Cirrus that’s not high enough to pull the CAPS parachute handle and I wasn’t able to maintain altitude. I knew I had to perform a forced landing. I picked a field, ran through some quick shutdown checks, got full flaps out, and managed a touchdown which in the real world I hope would have been survivable.

And took a breath.

“Happens fast doesn’t it”, Mike said behind me, startling me a little as I’d been so absorbed in the situation I’d kind of forgotten he was there.

“It sure does” I responded.

For the next hour Mike then put me through more scenarios including engine failures above 600ft AGL (where I could pull the CAPS handle and descend under the parachute), engine failures above 2,000ft AGL (where I could troubleshoot to try and restart the engine before pulling the handle). We also went through an exercise on how to account for wind direction when descending under the parachute in a Cirrus so you can position the aircraft before pulling the chute to maximise your chances of drifting towards and landing in an open space, and some unusual attitude recovery techniques.

Then he put me back on the runway and pressed a few buttons turning my sunny day in Moorabbin into a cold, grey, overcast, morning. Or as we call it, “Melbourne”.

Full power, eyes on my airspeed, “airspeed alive on both”, that looks OK. “Engine temperatures and pressures in the green”. “Rotate”. I lifted the SR22 off the runway, up above 600ft calling “CAPS available” as I climbed into the grey mess in front of me. Eyes down in the cockpit flying solely on instruments. Turning onto my outbound heading and climbing further, everything humming along nicely, this was good. Some real IMC practice.

Up over 2,000ft nothing to report. I’m now thinking “what’s going to happen? Surely something’s going

to happen”.

Something happened.

The tone of the engine started to reduce, just a tiny bit, but enough to be noticeable. Then it dropped a little bit more. Looking at the gauges I could see my engine power output reducing, but I had no idea why. “Lower the nose a little to maintain airspeed Stef” I said to myself. This is one reason why I always climb at an indicated airspeed on autopilot rather than using a vertical speed per minute, to avoid an autopilot stall if my speed starts to decay.

But my power kept reducing and I couldn’t see any reason why it would be doing that. So I lowered the nose a little more, then a little bit more, until I had lowered it so much that I was no longer climbing in fact starting to push over into a descent. Fuel tank change, mixture sweep, fuel pump was already on so I turn it off and on again. No change, down we go.

Again, this was one of those partial failure moments. A slow, steady transition from “everything’s great, time for a snack” to “I can’t keep this thing in the air anymore”. And at some point in there you have to start making decisions.

What to do? My brain summarised the situation for me: “Well you can’t climb, you can’t maintain a level, so you’re going down one way or another Stef”. Thanks a lot brain. “You’re still in cloud, you can’t see the ground, you can’t get the engine going, you’ve really got one choice mate”. Stupid sensible brain.

Two thousand feet AGL I pulled the CAPS handle. Down we floated into another pixelated field.

“What happened there?” I said out loud.

Mike explained that I had been climbing through an area of severe icing which had quickly started freezing over my air intake, therefore reducing the power output of the engine. I could have opened the alternate air, but my brain never took me to the place where I had considered air intake icing as a reason for the lack of engine performance. So the alternate air intake switch never registered as an option.

That was enough for me. Two hours into the session my brain was done. We called it a day, Mike put the kettle on and we debriefed the morning’s events.

I didn’t think I’d performed badly – by the end of the session I felt like I was managing the situations fairly well. But what I hadn’t expected was how long it would take me to react to each situation to determine what was happening and what the best course of action should be each time. I also hadn’t entered the simulator session expecting to be confronted with so many different types of emergency situations. We’re often trained to react to the big ones such as a total loss of engine power but not always the “medium” ones such as partial power failures, electrical system issues, or gradual build-ups of ice.

I went into the simulator a fairly confident YouTuber pilot with an idea for a video. I exited with a far more realistic appreciation for my skills in emergency situations and a clear realisation that simulator training could actually save my life one day.

So why do we private pilots sometimes avoid this type of ground-based training? Do we think we already know what to do in an emergency situation so sitting in a sim is a bit of a waste of time? Are we worried about making mistakes and showing our weaknesses in front of another pilot? Perhaps we’re worried that if we make big mistakes in a simulator we will question if we really should be out there flying in the real world at all. Isn’t it easier to avoid the whole thing and if something happens in the real world just “work it out”?

If it’s any consolation, I thought all of those things before this session.

I certainly think differently now.

Now my opinion is this – get all of your mistakes out of the way in a box that’s bolted to the ground. Expose your weaknesses, be honest about what you don’t know, get pushed to the point of failure. Making errors in a sim is A GOOD THING.

Then if your instructor berates or judges you for making those errors, get a new instructor. Simple. Do a session like this with someone who helps expose those weaknesses then helps you understand why you made the decisions you did, and how you could do it better next time.

Oh and one other thing – if you book a session in a sim don’t just treat it as a one-off thing. This should be part of your regular ongoing flying experience. It’s not just “routine flight training”, it’s essential flying experience. Simulator sessions aren’t just something you do every two years before your BFR, but should be part of your ongoing experience. If you’re due to fly but the weather is bad, or if your plane is in for maintenance, ask if you can do an hour of emergencies in the sim instead of going home and watching YouTube.

To flying schools – encourage students to do regular sessions in the sim. Maybe offer reduced hire rates if students have done a certain amount of sim sessions with an instructor beforehand. Or use the coffee card idea: do four sim sessions get the fifth one free, call it a Sim Card (I’ll see myself out).

Here are three things I do differently now after the sim session:

I ALWAYS call out airspeed, engine conditions, and static RPM on my takeoff roll. I’m basically looking for a reason to abort my takeoff right through the roll and climb-out.

I brief a forced landing spot (usually via Google Maps on my iPad) at the end of the active runway in case I can’t maintain altitude below 600ft and need to land straight ahead. A golf course, or a park, or the best open space I can see so I know exactly which way to turn instantly if something goes wrong.

I’m going to start including sim sessions as part of my ongoing flight experience. Not just before an exam or a test, but whenever I wanted to go flying and couldn’t, or simply whenever I have one of those “what would I do if . . .” thoughts.

One final point, you don’t need to do this in a fancy full-motion simulator like I did here. Even basic scenario-based training in a classroom with an instructor and a whiteboard is incredibly valuable. We can all be guilty of thinking we’ll “work it out” if something happens, but ground-based simulations of those “somethings” give you an opportunity to expose your weaknesses and then take time to evaluate those gaps in your experience before it happens for real.

Time is going to be the one thing you never have enough of in a real emergency, so consider investing a little of yours in a simulator session the next time you’re at the airport.

VIDEO: Some of the scenarios experienced in full-motion simulator from Stefan Drury’s YouTube channel. In addition to YouTube, Stefan Drury is also on Instagram and Twitter.

This story first appeared in the July 2019 edition of Australian Aviation. To read more stories like this, subscribe here.